One Drink Too Many

by Benjamin Pomerance

The main stem of the Boquet River starts its journey in the heights of Dix Mountain, towering above the Adirondack village of Keene. From there, it drops precipitously, losing altitude quickly on its downward journey into the communities of Willsboro, Whallonsburg, Wadhams, Elizabethtown, and Lewis. For anglers, the waters are resplendent with salmon, along with brown and brook trout. For photographers, scenic vistas are plenty.

And for Captain Daniel Pring of the British Royal Navy, that waterway felt like an aquatic path to the promised land. Near Willsboro Falls stood a stone mill, filled to the rafters with sacks of flour. The British needed flour, and Pring intended to help himself to everything that he and his men could carry away from that storehouse. If they could find other edible items, they would take those supplies, too. Anyone who tried to get in their way would get a musket ball or a bayonet in the ribs. Nothing would stop his men from taking what they needed.

From Rouses Point the British flotilla sailed on the calm waters of Lake Champlain, led by the mighty brig Linnet and followed close behind by six sloops and schooners and 10 row-galleys. In four months, this group of ships would see action on this lake again, exchanging fire with the plucky Americans in Plattsburgh, ultimately defeated by the tactical cunning of Commodore Thomas Macdonough. Pring would command the Linnet during that battle in Plattsburgh, attacking the head of the American line, fighting until his ship was at risk of sinking.

But no one in Essex County on May 13, 1814, could forecast such an outcome. For now, Pring and his men belonged to the most powerful navy on the planet, expecting no resistance from some rank American amateurs. For now, the Linnet was a grand fighting ship, built in the British shipyards in Canada and considered unbeatable in combat by His Majesty’s military leadership. And for now, nobody in the little town of Essex wanted to see a gang of British vessels gravely bound toward their shores.

The Redcoats were not strangers on these lands. Winslow Cossoul Watson’s Military and Civil History of the County of Essex, New York, published in 1869, states that “the enemy appeared on several occasions in the waters of Essex County.” Residents of Essex and the nearby community of Willsboro knew what havoc these military men could wreak in their streets, their businesses, and their homes. It was therefore likely that a combination of loud curses and fearful whisperings met the first sightings of Pring’s flotilla on May 13, coming into view around 2 p.m.

Yet there was apparently another type of reaction to the arrival of the warships: the response of a child who somehow knew what he was seeing and what he needed to do. Watching from the shoreline, young Elihu Higby took stock of the ominous sight and ran for his father’s place of business. Like an instant replay of Paul Revere’s midnight ride at the dawn of the American Revolution, the boy began shouting as soon as his father came into earshot, “Pa! Pa! The Britches is coming! The Britches is coming!”

Levi Higby, patriarch of the Higby household, stopped what he had been doing and stared at his frightened son. He could tell from the look of horror on Elihu’s face that this was no joke. And he could take a pretty good guess at what the British were after. He was a merchant himself, the owner of forges that were at that moment creating the anchors for American warships and the proprietor of a distillery that was at that moment making grog for American sailors to drink. The British were seeking supplies, Higby surmised, and they would kill to get them.

Nearby, Higby knew, a well-regulated militia stood ready to defend their lands and their families. Brigadier General Daniel Wright, a Connecticut native, had amassed an extraordinary war record during the Revolution: fighting at Bunker Hill, leading a regiment at Fort Ticonderoga, and then serving at the pivotal Battle of Saratoga, where he witnessed the surrender of British General John Burgoyne. In 1798, while continuing his military career, he had opened an inn and tavern in Essex, quickly becoming one of the most popular men in town.

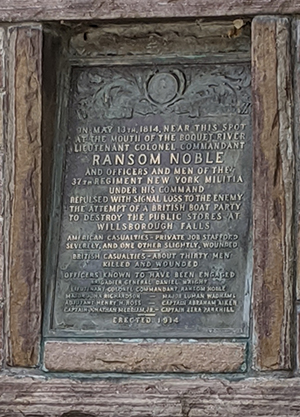

As a result, when the fledgling United States declared war on Great Britain in 1812, Brigadier General Wright evidently had little trouble recruiting a regiment of men from Essex, Willsboro, and neighboring communities, and training them into a fighting force. On the May day when Pring’s warships showed up on the shoreline, however, Wright was away on business. Yet he had left an able soldier in command: Lieutenant Colonel Ransom Noble, another prominent merchant who operated a tannery, a general store, and various other enterprises.

An outside chance therefore existed for the local military men to drive the British out of their midst. But Higby remained plagued by one fundamental question: how to alert Ransom Noble that the British were coming ashore. Given the limitations of communications in 1814, no options seemed to be available. Then, out of nowhere, an improbable plan started to hatch in his mind. Initially, the notion seemed crazy, potentially placing his life and the life of his family at risk. Yet the more he thought, the more he decided that the risk could be worth the reward.

He sent Elihu home, likely in the company of an employee from the distillery, along with a message that outlined the scheme to his family. Each of them would have a part to play, and all of them would need to act out their roles perfectly. He asked his wife and children to quickly prepare a feast fit for the King of England himself, to set their table with their finest utensils and decorations, and to make their home as beautiful as if royalty was about to visit. Then he took the keys to his ironworks and headed into town to meet the invading military force.

Meanwhile, the British had dropped anchor off of Split Rock and traveled up the Boquet River in their row-galleys, leaving behind some of their men to guard the bigger ships in the lake. But when they reached land, they found a startling sight awaiting them: a man offering almost comically lavish remarks of welcome. It was Levi Higby, insisting that the nautical men do him the honor of visiting his forges and seeing how he made his anchors — and then declaring that his family would provide them with a banquet of food and drink as a reward.

The sailors stared at each other, scarcely believing their good fortune. Nothing in their military training had prepared them for something like this. Incredulous, they accepted the man’s proposal.

The tour of the iron forges took plenty of time, lasting long enough for Higby to surreptitiously tell someone — perhaps one of his employees — to get word to Ransom Noble right away about the British invasion. Upon hearing the news, Noble immediately sent word to Brigadier General Wright, and then summoned the members of the militia to prepare to mount an attack. As the local men grabbed their weapons and answered Noble’s call, their foes were finishing their visit of the foundry and walking frivolously toward the Higby homestead.

Mrs. Higby and the children had indeed followed Mr. Higby’s prompting perfectly. At their home, an abundance of vittles met the arrival of the British, who did not need to be asked twice before tearing into the meal. Then Levi Higby brought forth the grog from his distillery, the same grog that never failed to boost the morale of the American seamen, and the British sailors’ eyes really widened. Soon, they were drinking toasts to the King and to each other and to their benevolent host, downing the mixed liquors as if they were water, happy and secure.

Precisely what happened next is unclear. Some accounts suggest that the British commander suddenly grew suspicious of the abundant Higby hospitality and ordered his men to leave. Other chronicles indicate that Recoats simply walked out of the Higby homestead, bellies bulging and heads swimming, and tramped right into an awaiting lion’s den. Yet both versions of the story reach the same conclusion: the Essex County militia waiting to escort the stuffed and inebriated British back to their boats under a hailstorm of musket balls.

Those sailors who were not felled by the muskets took off rowing at full speed as soon as they reached their galleys, with the militia pursuing them along the Boquet River’s wooded shoreline. Soon, the furiously rowed boats had outpaced the running militia members, and the stunned British breathed a sigh of relief.

But when the galleys reached the larger gunboats in Lake Champlain at the mouth of the Boquet, and the sailors were climbing back aboard — without a single sack of the flour that they had been assigned to steal — the sharp-eyed servicemen realized that their troubles were not over. On the banks overlooking the waterways swarmed the Essex County militia men, seizing the strategic advantage of the high ground, just as they had been trained to do.

Pring ordered the crew of the Linnet to fire upon the militia members, and the ship’s guns roared away. Yet the commander had overestimated the range of his own weapons. The cannon balls crashed harmlessly into the sides of the banks, leaving the members of the militia unscathed. Then the Americans opened fire, finding that the bright uniforms of the British sailors on the ships far below them made easy targets. Horrified at the vulnerability of their position, Pring was forced to give the order to retreat. Essex County had been saved.

In a letter to New York State Governor Daniel D. Tompkins dated May 15, 1814, Wright wrote with a flourish about the militia’s improbable victory. He extoled the leadership of Ransom Noble and declared that all of the men had performed under fire like seasoned combat veterans. His unit had suffered no deaths and only two men wounded, while inflicting casualties of “about 30 men” killed or wounded upon their enemy.

Yet there is a potential irony — or perhaps a potential accuracy — in Wright’s description of the battle. As historian David C. Glenn points out, the Brigadier General’s account of the fighting makes no mention of Levi Higby, saying nothing about the family luring the British with food and alcohol, trapping them for the Essex County militia to attack. Perhaps this is because Wright wished to keep the focus of the victory on the militia members whom he had trained, not wanting to cede any credit to a cunning civilian. Or, perhaps the absence of this story in Wright’s records is due to the fact that it did not exactly occur in the manner described above.

In the Willsboro Heritage Society’s archives today resides the records of the Higby family, which recount their purported role in all of its made-for-Hollywood glory: the running and shouting of young Elihu, the clever plan of wise Levi, the beautiful banquet placed before the unsuspecting British, the use of grog from the Higby distillery to soften the sailors’ wits in time for the militia to attack. And so a historian’s dilemma emerges: two narratives, each conflicting with the other on salient details, neither emerging as the perfect source to believe.

Further discrepancies exist among writers of the time. Watson’s history, for instance, has the Battle of the Boquet River occurring one year earlier, in 1813. Some newspapers place the British invasion in Essex County on May 13, the date commonly accepted today, while others list it as May 14. No one is able to resolve these disputes today, of course. Lieutenant Colonel Noble’s former store is now a library. Brigadier General Wright’s celebrated inn is now the Essex Town Hall. The Higby family rests together in Willsboro’s Memorial Cemetery.

And the Boquet River keeps on flowing, the water rushing over the same pathway that the oars of British galleys had churned in 1814, still silent about what happened on that fateful day. But this much is clear: the Essex County militia — which would serve valiantly again at Plattsburgh just a few months later — scored a victory over the British on that day with bravery and strategic mastery. And maybe, just maybe, they were helped in that cause by a child’s cries and a father’s ingenuity, sending their foe back up the river again after one drink too many.

The author thanks David C. Glenn and the other archivists of the Willsboro Heritage Society for preserving records and information essential to keeping alive the memory of the Battle of the Boquet River and the service of the Essex County militia in the War of 1812.

This story was originally printed in the Lake Champlain Weekly, a Studley Printing publication. For more information, visit www.lakechamplainweekly.com.